How can we help?

888-283-1722

Call us now at 888-283-1722

24/7 Referrals and Nursing Support

Voices of Care Blog

The Edge of Grief: A Summer Reflection

Posted on September 28, 2015 by Care Dimensions By Ellen Frankel, LCSWThis post originally appeared on the Huffington Post.

"The pain passes but the beauty remains." -- Pierre August Renoir

Will it ever stop hurting so much? Will we ever get over the grief?

These were the questions being put on the table by participants in a support group I was facilitating for those who were recently bereaved. They debated the often cited notion that time heals all wounds, for the wounds they brought into that room were large, deep gashes, raw and oozing and too tender to touch. It was nearly impossible for most of those present that night to imagine a time when the pain would ever be bearable. There was "before" and now there was "after." The death of their loved one turned their hearts inside out, and their lives upside down.

As a bereavement counselor, it is my job to help create a safe space to give voice to the unspeakable, and to companion others in their grief journey as they travel into the wilderness of their soul in search of their own inner knowing and truth.

But it's a messy business, this grief work. There is no GPS saying where to turn, or when to recalculate, or when you will ever arrive at your destination.

One man asked, "Does it ever go away, this pain? Do we ever really heal after losing someone we loved?"

His question resonated with the group members and they began discussing and exploring with one another. One woman, whose mother died a couple of months prior asked another member who had lost her loved one nearly a year ago if the grief changes at all, and if so, how? While they talked, I listened. Then a group member turned to me and asked, "What do you think? Do we ever get over the pain of our loss? Does the grief ever end?"

I waited a moment, thinking how I wanted to respond as their group facilitator, but before I could get the words out of my head, my broken heart answered from its own truth instead. The words came from my heart as a daughter whose father had died a year ago, and as I spoke them, I heard them for the first time.

This is what I told them:

When you break a glass on the kitchen floor, you have to be careful when you go to clean up. The glass is sharp -- so very sharp -- so as you pick it up, piece by piece, you have to go slowly, touch the glass cautiously, because even the slightest encounter with the edge can pierce your skin and you hurt and you bleed. The shards of glass are harsh and the edges cut deeply.

Now imagine that those broken pieces of glass have been thrown into the ocean. They are at the mercy of the current, and have to let go into the forces of nature. Some days the ocean roars with big forceful waves and the glass is tossed and churned and thrown along with the rocks and sand. Other times the ocean is gentle, and the glass is stroked by the rhythm of the tide. Yet just as the gentle ocean lulls the glass with its soothing melody, another storm hits and the glass is once again pushed against the force of currents, the force of the moon and the heavens. And yet again, at some point the ocean quiets, the flow is once again soft, the waves flow like the inhalation and exhalation of the breath, arriving at the shore, hugging the sand.

And at some point, there you are, on a warm, sunny July day, walking along the seashore when you stop because just in front of you, sitting amidst pebbles and rocks and periwinkle shells is a piece of sea glass. You bend down to pick it up, marveling at your good fortune to find this treasure. Holding it in your hands you feel its smoothness and the places where the sea glass might have a slight ridge. You can rub it on all of its sides, for no longer are there sharp edges. Instead, the edges have become solid and smooth and you can hold it tightly in your hand without fear of injury. In fact, holding it in your hand feels fortifying and strengthening. We actively seek these brilliant pieces of sea glass precisely because they echo the beauty of survival, of resiliency, and of hope.

With tenderness and love you are able to hold this piece of sea glass and learn its unique features. Where once the edges of the glass were jagged and sharp, now the edges are ever softly rounded, so that you can run a finger over them repeatedly, and it will not take your blood.

That is how grief can change, I told the group members. Those are the edges of grief.

Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, the great Chassidic Rebbe said, "Nothing is as whole as a broken heart." I think that is why so many people on the beach, children and adults alike, feel that finding sea glass is like finding a treasure. When we hold a piece of sea glass, we hold in our hands what was once part of something broken, something that was sharp and painful to the touch. When we hold it after its time of being housed in the ocean of life, it becomes stronger in the broken places and each small piece we find tells us that we too, are a treasure. We too can grow stronger from our grief. A friend of mine, who lost three family members within a two-year period, told me that each loss has made her a kinder person. Each loss has made her softer at the edges.

I looked into the faces of the group members, and we all took a moment to look at one another and breathe. Our broken hearts understood this in a way that allowed us to look at the gnawing gash of our wounds and understand that even in our pain, healing had already begun. Even in our most piercing and painful moments, the edges of grief are touching the forces of nature, the ebbs and the flows, and in its own time, there would be a grief that we could hold as a treasure of love, of memories, of beauty and connection.

Ellen Frankel is the author of numerous books including the novel Syd Arthur, about a middle-aged, suburban Jewish woman and her search for enlightenment 2,500 years after her namesake Siddhartha, the historical Buddha.

Additional Posts

6 Tips for Coping with Loss During the Holidays

Posted on November 21, 2024 by Care Dimensions Bereavement TeamHere are some ways to help you find some comfort and even happiness as you navigate the holidays without your loved one. ...

Continue readingActivities that Help Grieving Children and Teens

Posted on November 14, 2024 by Sarah Bujold, MS, CCLS, & Jason Abrams, Child Life Practicum Student in ChildrenChildren and teens often benefit from creative activities that allow them space to process their feelings, develop coping skills, and remember the person who died. ...

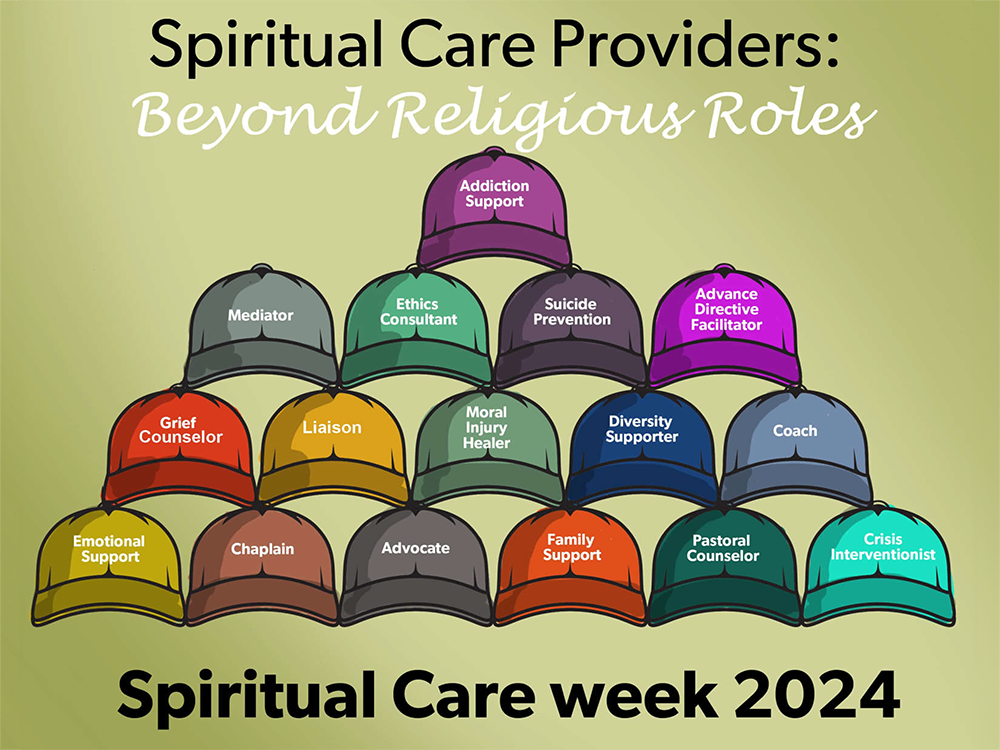

Continue readingSpiritual Counselors: Beyond Religious Roles

Posted on October 21, 2024 by Rev. Sharon Dunbar-Link, M. Div. in HospiceWhen working with hospice patients and their families, spiritual counselors wear many hats. Learn how we support patients beyond traditional religious roles. ...

Continue readingAnyone—patient, family, care provider—can make a referral. Fill in the form online or call us today.

Since 1978, Care Dimensions, formerly Hospice of the North Shore, has provided comprehensive and compassionate care for individuals and families dealing with life-threatening illnesses. As the non-profit leader in advanced illness care, we offer services in over 100 communities in Massachusetts.

Copyright 2025 | Care Dimensions, 75 Sylvan Street, Suite B-102, Danvers, MA 01923 | 888-283-1722 | 978-774-7566 |